My God my bright abyss

int which all my longing will not go

once more I come to the edge of all I know

and believing nothing believe in this:

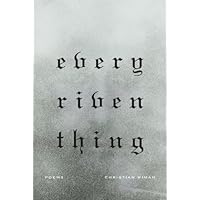

And there the poem ends. And this unfinished poem is the beginning of a remarkably moving, wise and luminous book. Christian Wiman is a poet critic and a poet whose writing sometimes sounds as if each word is melded onto metal like arc welding. The image is deliberate; in his latest collection, Every Riven Thing, Wiman's poetry flashes with quite remarkable intensity, urgency and honesty in the face of human mortality.

This is Wiman's first published collection since he was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, and given a future with just enough hope to make each day a gift, and each tomorrow precariously uncertain.

There comes a time when time is not enough:

a hand takes hold or a hand lets go; cells swarm,

cease; high and cryless a white bird blazes beyond

itself, to be itself, burning unconsumed.

Poem after poem, Wiman looks straight into the ambiguity of things and the contingency and givenness of circumstance, the fragility and tenacity of our hold on life, and tells what is seen, or not seen. What gives these poems their unsettling potency, also ironically makes them vehicles of hope and future possibility. Wiman believes in God. But forget faith as panacea, or God as postulated rescuer. This is faith rooted in a willed agnosticism about the providence and purposes of God. God is not the answer, but the question; God is not the solution, neither the problem. God simply is, but is to be trusted. There is a 'though he slay me yet will I trust him' defiance in some of these poems that carries far more authentic currency than thick volumes of so called Christian poetry. Here's a sample:

This Mind of Dying

God let me give you now this mind of dying

fevering me back

into consciousness of all I lack

and of that consciousness becoming proud:

There are keener griefs than God.

They come quietly, and in plain daylight,

leaving us with nothing, and the means to feel it.

My God my grief forgive my grief tamed in language

to a fear that I can bear.

Make of my anguish

more than I can make. Lord, hear my prayer.

Rarely have I read 21st century poetry that comes so close to the best metaphysical poetry of the 17th Century. George Herbert would have been proud to write that, except I doubt there was an ounce of pride in that country parson. But here is a poem that is complaint and prayer, lament and petition, human voice and words seeking divine understanding and help. It is hard to imagine a more luminous darkness than is contained in those 11 lines of a heart's suffering, having had enough.

I've always argued that the finest poetry takes us nearer the pastoral realities of Christian ministry than most any other literature. Reading that poem we are allowed to look inside a heart afraid to trust and afraid not to, anguished at the thought of death and holding on to hope in the God who accompanies the grief – an d we rightly take of our shoes, and kneel. This is poetic truth distilled from a courageous soul. Another poem, 'Hammer is the Prayer', which begins, 'There is no consolation in the thought of God', then works towards precisely what consolation there kight yet be, and finishes with the couplet:

peace came to the hinterlands of our minds,

too remote to know, but peace nonetheless.

If I were to attempt any summary of these diamond cut poems, these two lines would have to do. They are the poet's own words, and as he goes on living, writing, fighting and working, may he know 'peace nonetheless'.

( This book is not reviewed for the publisher or any Journal – it's reviewed here simply because I think his work deserves to be better known.)

Leave a Reply