Education is about opening doors – doors of vision, opportunity, possibility, understanding. Not that I thought this while I was being a nuisance at Secondary School, and giving the French teacher a particularly hard time by deliberately mangling spoken French with an exaggerated Lanarkshire accent that must have sounded like a gearbox change without a depressed clutch.

When a few years later, having got Higher French at night school, I took French Studies at Glasgow University, I didn't expect that particular subject to provide some of the richest educational experiences of my student days, and on into my life. But that's what happened. For two years I studied the novels of Camus including his masterpiece, La Peste, read Le Figaro and followed the current affairs of France in 1971-2.

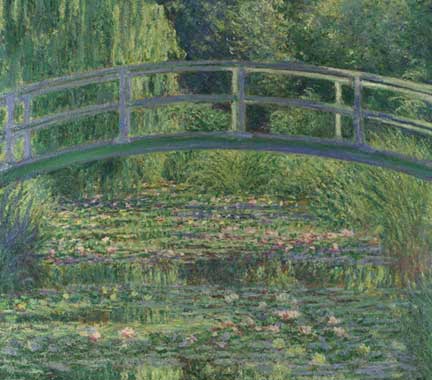

We reviewed 20th Century French Art such as Impressionism and post-Impressionism, cubism, dada and surrealism, and French Theatre including a study of Les Mains Sales by Sartre, the history of the French Republics, the political career of De Gaulle and the relations of France to Europe and its colonies. Immersion in the literature, history and language of another European nation was a profound intellectual experience of new perspective, sharpened perception and freshly cultivated sympathies. I am so glad I took that course; it made me a better human being by introducing me to the reality of worlds other than my own, and helped to shape me as a pastor in ways theology never could.

Amongst the lasting voices from that course is Antoine De Saint Exupery. I read Vol de Nuit, (Night Flight) and immediately discovered a writer who wrote of loneliness, achievement, challenge, humanity. For Saint Exupery earth and sky are elemental realities, but also metaphors for those human experiences by which we grow and change, attempt and fail, take risks and fly or fall. His Wind, Sand and Stars contains some of the most beautiful reflections on human friendship that I know. Great writing has to have more than depth; it has to make you want to dive; writing that endures does so because it's living energy transfuses with the mind that reads it and shapes its future thought; transformative writing does not merely persuade or permit some new thoughts, it generates ideas, rearranges the familiar assumptions that furnish the mind, and fundamentally changes the way we think.

The first time I read Le Petit Prince I was taken aback by its strangeness. Yet repeatedly I found sentences and phrases and thoughts replete with that wisdom that is effortless, offhand, sentences of unremarkable words arranged with remarkable insight. Now some of its sentences have become familiar furniture in my own mind;

"What makes the desert beautiful is that somewhere it hides a well. "

"It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

"A goal without a plan is just a wish."

“A rock pile ceases to be a rock pile the moment a single man contemplates it, bearing within him the image of a cathedral.”

I doubt I would have discovered Saint Exupery if I hadn'e been compelled by an MA course structure to take a modern language, and opted for French Studies, and without knowing what I was doing, opened doors – doors of vision, opportunity, possibility, understanding.